Ola Niepsuj

by: Maja von Horn

Illustration: Ola Niepsuj

Photography: Piotr Maciaszek

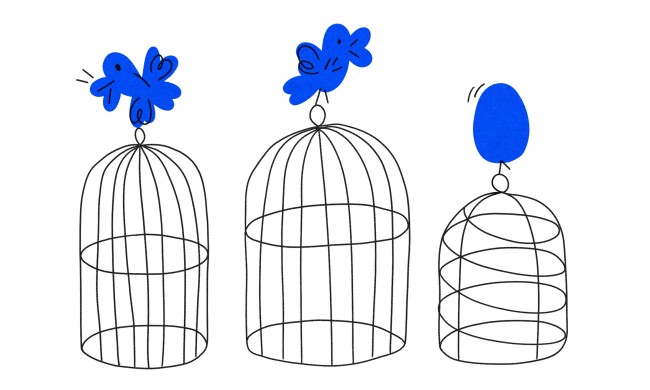

Whenever Ola Niepsuj uses her illustrations for the fight for gender equality, freedom or tolerance, she feels that her work has deeper meaning, that she’s not just someone who makes charming graphics. Drawing has always been a passion of hers. As a child, she and her brother would attend after-school art classes led by a pair of hippie students from the Lodz Academy of Fine Arts. It was them, along with her parents, who instilled in her a love for art.

More than a decade later, she graduated with honors from that same school, the department of graphic design and painting. She also studied in Portugal, at the Escola Superior de Artes e Design in Matosinhos and the fine arts department at the Universidade do Porto.

Today she is a versatile artist who creates illustrations for books and articles, designs posters, infographics, and visual identities for brands. Occasionally, she does work for the fashion industry, bringing her signature sense of humor and lightheartedness to her watch, sock, and underwear designs.

Her unique, funny style has been recognized in exhibitions around the world, including Japan, France, the US and the UK, Sweden, Germany, Italy, Bolivia, and Cuba. Her illustrations, which offer witty commentary on the world, have been published, among others, in The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. During our interview she is wearing a blouse with an oversize yellow collar flipped on top of a white sweatshirt. A collar like that tells you something about the wearer: they’re confident, don’t take themselves too seriously, and have a sense of humor.

Ola's exhibition “Tyle ile trzeba” (As much as necessary) at the BWA Gallery in Bydgoszcz

19.06.2020 - 01.08.2020

“Working with Americans I’ve learned how important it is not to perpetuate stereotypes”

Maja von Horn It’s been some time now since the breakout of the coronavirus pandemic. How is the situation affecting your work?

Ola Niepsuj Not much in my work has changed. I have several large projects, which I’ve been working on for the last several months, to finish. I have a studio in Mokotów, where I bike every day, no matter the weather. Getting there takes me seven minutes. I don’t touch anything or meet with anyone on the way.

M.v.H. You’re not worried that it will be harder to get an assignment?

O.N. I have several regular clients, thanks to Marlena Agency, my representatives in New York. They do work in the US, Canada and Australia and they specialize in finding European illustrators. We have a different visual language, aesthetic, and narrative style from American illustrators.

M.v.H. How did you get involved with this agency?

O.N. I sent my portfolio to a number of English-language agencies, including ones in Scandinavia and the UK. I was referred to the one in New York by Agata Endo Nowicka, who works with them as well. That was more than eight years ago, when illustration wasn’t as well-established as it is today. There weren’t a lot of us, and we all knew each other. The meeting went well, something sparked, and we started working together.

M.v.H. Your illustrations have been published by, among others, The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. That’s a big deal.

O.N. I had just graduated from the department of graphic design and painting at the Lodz Fine Arts Academy, so I felt very valued. These initial publications in the US press give you a boost of confidence. I remember when friends would send hard copies to me in Poland, so I could have them as a souvenir. I still keep them in a box. I get very excited by getting published in the press, it’s very important for an illustrator. It gives you prestige and attracts commercial clients.

M.v.H. Who are your regular clients?

O.N. For instance, Azlo, an American start-up that specializes in online banking for small businesses. I’ve been working with them for about a year. We’re trying to familiarize people with online banking, explaining difficult issues with the help of illustrations. They’re a very gutsy client, who chose the most experimental of my proposals. Until now, I’ve felt there is a difference between assignments that I get from Europe and those from the US. Europe is more artistic, willing to take more risks, to experiment. The US is more commercial, careful, balanced, as well as more sensitive to the questions of equality, political and gender correctness, parity. This makes the work a bit more conservative.

M.v.H. One of your foreign clients is the publisher Taschen, with whom you’ve been working for two years. How did you convince them that you were the right person?

O.N. I designed for them five travel books that were written by New York Times journalists. With assignments like this, an agency gets several people to put forth their proposals. Everyone gets the same subject, 24 hours to present their concept, and after this, the client gets to choose whom they want to work with. The illustrations I proposed are completely different from the ones that ended up in the books. They were “smoothed out” for the global market. It’s probably not my best design in terms of substance or creativity, but it's scale dwarfs any other assignments. I get the books on pallets from China -- new versions in different languages -- English, German, Spanish, French. I’ve learned a lot while working on this project. Because of its global scale, every drawing had to go through a political correctness edit. They checked if the figures I’ve drawn for people living in a given region had the right skin tone, whether the illustrations maintained gender and racial equality, whether any of the figures were not showing a gesture that could be offensive somewhere, etc. In Poland, we don’t think about this as much, but working with Americans I’ve learned how important it is not to perpetuate stereotypes -- like instead of showing a woman with Asian features as a computer programmer, we can show her having fun on a jet ski.

M.v.H. You’re a very versatile artist, you work on film posters, on illustrations for books both for children and adults, do industrial design, and even fashion. Do you have a favorite medium?

O.N. If I were to do only one thing, I’d quickly get bored by my job. I’d also be worried that I was repeating myself. Whereas now, in the morning I do the typesetting for an album about Pope John Paul II, in the afternoon I illustrate a vegan cookbook [the latest edition of Jadlonomia - ed.], later I illustrate a book about Polish design and then, to cap the day, an article for the journal Nature about bacteria in the big intestine. There’s no boredom. When it comes to the medium, my favorites are typography and illustration, which interact most seamlessly when I work on posters. I love working with writing, like illustrating news articles, content for children, designing covers and infographics. I find the research phase most interesting. I love to dive into topics that I wouldn’t have otherwise. The more obscure, the better. I remember when I had to find out everything there was to learn about dinosaurs to illustrate a book for kids. There is no room for error, you can’t fool a five-year-old. A Spinosaurus obviously has to be larger than a Triceratops.

M.v.H. What kind of projects do you reject?

O.N. Those that don’t agree with my value system. I refuse to illustrate books or projects that perpetuate stereotypes, that go against values such as equality or freedom.

M.v.H. You tell them honestly that you have a problem, or do you simply refuse?

O.N. If I see that there is an opportunity for dialogue, I voice my concerns. If the publisher is open, sometimes I’m able to convince them. For example, they agree that the mayor in a children’s book should be made a woman instead of a man. Children absorb a lot, I think it’s an important element of civic education.

M.v.H. Does this ever happen to you: you get an assignment, the client is waiting for your proposals, and your mind is blank?

O.N. Of course, I’m only human. The larger and more important the project, the more often I get stuck. When I know that something will have a large audience, I feel the pressure, and that’s when the artist’s block appears.

Jadłonomia po polsku

Marta Dymek, illustrated by Ola Niepsuj

M.v.H. What do you do?

O.N. I go back to the methods I teach my students in my workshops. I make an association diagram, I ask myself questions: who is this for? What is it for? What is it supposed to be? What medium should I use? It takes practice to find ideas. It’s a job like any other. The tenth filling a dentist has ever done might not be that great, whereas the thousandth they’ll be able to do blindfolded.

M.v.H. But isn’t creative work different? You can run out of ideas.

O.N. With time, you learn how to quickly find connections, use your cultural knowledge. Translating this into the actual drawing is the last phase.

M.v.H. Is self-discipline a strong suit for you?

O.N. I try very hard, but being a freelancer is very difficult, and being an artist freelancer especially so. It’s hard to clearly say how much time you devoted to a certain job. I am disciplined when it comes to documenting my work, taxes, contracts. I do everything by myself, I like to be in control of the business side. Only when I have more than twenty assignments at once do I hire someone to help. I don’t even have time to make myself a website.

M.v.H. That’s right, you don’t have a website!

O.N. The shoemaker’s children go barefoot.

M.v.H. It’s because you don’t have time to do it?

O.N. I’m starting to overflow with finished projects, since I document and archive everything. I’m more fascinated by my new assignments, than digging through old ones.

M.v.H. You simply don’t need a website.

O.N. I learned from my parents that one happy client is ten more future ones. I never had to look for work. But I’d like to start the website and collect all my work there. Even my boyfriend hasn’t seen all of it.

M.v.H. Speaking of parents. How was it growing up in the apartment blocks of Lodz in the nineties?

O.N. At the time those buildings were part of the landscape. I didn’t feel like I was any different. My father has a degree in architecture and construction, my mom also has a degree in construction. They’ve been running an industrial architecture business for years. They specialize in factories that manufacture pharmaceuticals. My brother Piotr, who is two years older, also has an architecture degree but he became a successful photographer, based in Milan. Pretty early on, right after elementary school, we moved into a house that my father designed. The neighborhood was brand new, there were no roads, and we’d hunt for treasures in empty lots and construction sites.

M.v.H. What did your childhood look like?

O.N. Our parents introduced us to art as young kids They took us to all the art exhibits they could find. You could see that they themselves were fascinated too, that they needed this escape from the everyday realities of the nineties.

M.v.H. Where would you go?

O.N. To the Atlas Sztuki gallery on Piotrkowska, for example. They had these great exhibits of abstract graphic design. My dad still collects those pieces. We’d also go to the City Art Gallery in Łódź, International Triennial of Tapestry, and shows at the Poznanski Palace where they’d get the works of Picasso and other great artists on loan. Sometimes my dad would also take us to art auctions. That was a lot of fun. As young kids, we attended drawing classes led by this wonderful couple, Jolanta and Piotr Mastalerz. When I was a university student, I realized that they were going through an art school curriculum with small children. These classes were so good for our development. I think every kid should have them at school. Sculpture, glasswork, ceramics, photography, art history. They’d drop supplies on the table and say “today we will be making a rhythmically-closed composition.” It was a very hippie affair, in the attic of their own apartment.

M.v.H. Did you go to art school because of them?

O.N. I never thought about that, but it was for sure an important impulse. I knew that I still had a lot to learn. Thankfully, in Poland art schools still offer high-quality general art classes -- painting and drawing, sculpture and composition. They skip that part of the curriculum in schools abroad, and it gives you a very solid foundation. You have to be able to paint a naked woman standing on a ladder, all of her bones have to be where they’re supposed to be.

M.v.H. While at university, you went to Porto for a year.

O.N. Yes, I did two semesters there as part of the Erasmus student exchange program. It was a wonderful experience, both for my education and just in life in general. The vibe at the school was very different -- the professors were young, working designers with their own studios. When they leave school, instead of reading the classics on their porch, they do their own work. They know the design programs and the business side of the job. I think that combining these two approaches is the key to success. The Portugese schools lack the basics, the craftsmanship, and the Polish ones don’t offer training in new technologies nor preparation for the job market. Fortunately, this is starting to change.

M.v.H. After you graduated, you went to New York to work with an underground theater. How did that happen?

O.N. When I moved to Warsaw, the costs of living completely overwhelmed me. My first roommate was Gosia Turczyńska, the photographer. There were times when we couldn’t pay for the internet and they’d disconnect it. Once, in order to send out a project I was working on, I had to go to a cafe. A guy at the table next to me kept snooping, looking over my shoulder. It turned out that he was an American playwright who came to Poland invited by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute and wanted to stage Polish plays at his Underground Festival in New York. He asked me if I’d want to design the theater’s visual branding. I took advantage of the situation, mostly so that I could go to New York. Along the way, I took part in a Polish illustration exhibit.

M.v.H. Was this a turning point in your career?

O.N. I think so. In New York I met a community of illustrators, and I became friends with some of them. That’s how I started traveling for work, doing shows and workshops abroad.

M.v.H. Which workshops were the most interesting?

O.N. I have the fondest memories of the one in Jerusalem, at the prestigious Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, where I taught for a week. I think I learned more from my students than they did from me. They have very interesting cultural baggage, completely different from ours. Right before the pandemic I led an illustration workshop at the academy in Riga and a poster art one in Budapest.

M.v.H. Which one was the worst?

O.N. In Tokyo. I learned a lot about Japan thanks to the workshop, how different visual culture can be. We had a big issue with the translation, because it seemed like the interpreter didn’t know design language. I gave the students an assignment using the word “space,” as in space on paper, in a drawing. I left for a couple of minutes, and when I returned, I saw that they were making paper sculptures instead of illustrations.

M.v.H. “Lost in Translation.”

O.N. Exactly! But I fell in love with Japan, its separateness. From Tokyo I traveled to Kyoto and several other places. It’s a visually fascinating country. The trip still inspires my work. Because the Japanese alphabet is pictorial, the logos are completely different. Japanese children draw isometrically, and not like us in the West, in line with the horizon, with a smiley sun up top. It’s fascinating, not only from the point of view of design. I went there six years ago, and I still look through the books I bought at a used bookstore, pictures I took of store signs -- and just yesterday, I wore pants that I bought at a second-hand store in Tokyo.

M.v.H. You have a great style which emphasizes your personality. Is fashion important to you?

O.N. I like fashion, sometimes I even design patterns, visual identities or packaging for different brands. Getting dressed is like putting together a collage -- I arrange fabrics that have different colors, textures, patterns, weights, and shapes into fun compositions. When it comes to my own style, I’m very picky. I don’t have a lot of clothes, but among those that I do own, there are no random things. I call my everyday look “the aunt from America” -- pants, sneakers, a sweatshirt, everything in a fun color palette. But sometimes I like to buy myself something extravagant. I wear only natural fabrics. I find all my clothing in second-hand stores. At university, I was friends with the fashion design students, and during every break between classes we’d go shopping for used clothing. I have some of the stuff to this day. They are indestructible. As a student of the Fine Arts Academy it was a faux pas to wear fast fashion. Regardless, I wouldn’t have been able to afford to get a stain on a new blazer or whatever. For the first dollars I earned, I bought myself Cole Haan x Nike shoes in New York. They look like I borrowed them from my grandma, made from brown woven leather with green stitching. Every time I wear them someone stops me on the street and asks me about them -- and not only old ladies! I like to surround myself with clothing and objects that are a bit strange, funny, that make me laugh. Weird things can be inspiring, and I like to pair them with classics -- like a stool shaped like a mushroom on a marble floor.

M.v.H. Two years ago, after you broke your leg, you had to use a wheelchair for several months. How did that affect you?

O.N. It was a deeply cleansing experience. You start appreciating how much freedom you usually have, like when you have to ask others to carry you to the bathroom at a restaurant. I think the pandemic can have a similar effect. People will start to notice and appreciate what they have -- parents will appreciate schools and daycares more, and everyone will appreciate the ability to leave their house without a mask, and to breathe in the smell of elderberry flowers. My dream is that we not forget how little we need. Recently I started to stop following news because of the pandemic. I know that when I read or watch too much bad news, I can’t later focus on work, I can’t draw something funny or make an illustration for a children’s magazine. I’m similarly unnerved these days by politics. In times of crisis I’m happy if I can support a great cause with my design work. Just like I reject projects that promote a different worldview from my own, I like to support those that are close to my value system. I take part in protests, I participate in awareness campaigns like those initiated by Democracy Illustrated [Demokrację ilustrowana], Graphic Designers for Medics [Graficy medykom], Thirty Years of Freedom [Trzydzieści lat wolności]. That’s when I feel that my profession can have meaning, that it’s not only for pleasure’s sake or to sell a product. It gives me a sense of mission and accomplishment.

Ola's favorite Instagram accounts

- Inspiration @micahlexier

- Illustration: @anttikalevi

- Graphic Design: @braulioamado

- Drawing: @shagey_

- Doodling: @molly.fairhurst