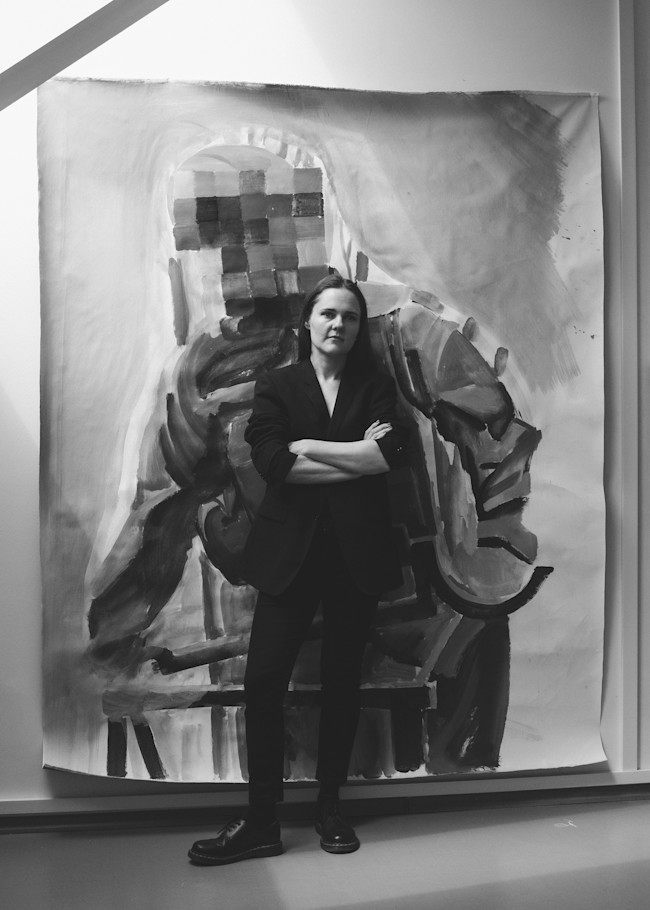

Lesia Khomenko

Text: Maja von Horn

Photography: Weronika Ławniczak

It makes a big difference whether a country has its own working artists or not. As long as it does, it’s still alive – says Ukrainian multidisciplinary artist Lesia Khomenko.

I meet Lesia Khomenko in Warsaw’s Ujazdowski Castle on one of the few sunny days in May, one month after her arrival in Poland. We walk up the castle’s staircase, which takes us to a bright attic studio that doubles as a bedroom for Lesia and her 11-year-old daughter Stefania. – I think it’s very romantic to sleep in the studio where I paint, it reminds me of Paris in the 19th century – Lesia laughs, and I am instantly charmed by this vision. The lodgings are part of an art residency that the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art granted both Lesia and her sister, also an artist. It would be difficult to find someone in her family with an ordinary 9-to-5 job. Lesia’s grandfather Stepan Repin was a Kyiv-based painter in the Soviet era. Both his daughters, Lesia’s mother and aunt, are architects. Both Lesia’s father and her sister paint and work with mixed media. And her husband Max, who is currently fighting the Territorial Defence Forces in eastern Ukraine, is a new media artist and musician. Her daughter, as soon as she is done with her online school, spends the rest of the day drawing. In her work, Khomenko reconsiders the role of painting as a medium, and constructs complex, critical statements around it. She is known for transforming her paintings into objects, installations, performances, or videos. Her works have been shown in many exhibitions around the world, including Miami, New York, Vienna, Warsaw, and most recently at the 59th Venice Biennale. – I had some doubts as a teenager whether art was the path that I had chosen for myself, or whether it was chosen for me. But then I realised that it didn’t matter. What matters is that [through art] I can make a statement.

Maja von Horn: How are you doing in Warsaw?

Lesia Khomenko: The residency has been great, but it’s ending soon. I’ve stayed here for almost two months – one month of my own residency, and one month of my sister’s. You can have your family with you, so me and my daughter have been staying with her. There is a big discussion right now in art circles about the need for these residencies [for Ukrainian artists] to be longer, ideally six or twelve months. When you’re given a place for one month, you end up spending a lot of that time searching for the next place to stay, instead of making art. But the residency team doesn’t push us to work. They suggested that we could use the time here to rest, which was very needed after listening to air raid sirens every night.

M.V.H.: When did you leave Kyiv?

L.K.: We left on February 25th, the day after the Russian invasion started. We spent the previous night sleeping in a shelter, and the next day we heard that Russian soldiers were getting close to Kyiv from the north. We were scared that they might surround the city, so we decided to leave immediately. I packed my family into my old Škoda Fabia – my mother, my husband, my sister, my daughter, our dog and our cat, and we went off to Ivano-Frankivsk, a town in western Ukraine, where we stayed for a month. My father, my aunt, and my grandmother stayed in Kyiv, because my grandma was very old and ill and couldn’t leave. She was a World War Two survivor, who had already escaped from Kyiv once. She couldn’t do it again. She passed away at the beginning of March.

M.V.H.: That is so sad.

L.K.: It really is. After that, my father and my aunt joined us, while my husband Max, who is a new media artist and a musician, registered himself with the army and was drafted right away. He is now in Territorial Defence Forces [the military reserve] in eastern Ukraine, where the worst fighting is taking place.

M.V.H.: I can’t even imagine how you must feel.

L.K.: He texts me every morning that he’s ok. But it’s so surreal. In Ivano-Frankivsk, my sister, who is also an artist and works mainly with fabric, volunteered to sew sleeping bags for the army, and did that for a couple of weeks. She spent every day sewing pieces of fabrics together – it was a therapeutic process, which protected her mind from going crazy. I volunteered with some art galleries, packing artwork. But then I came up with an idea to organise a residency, a space for artists to work. I started receiving some private donations from different artists from the West. In the beginning, I was forwarding these donations to some of my friends who are also artists and were left without money. Later I decided to collect this money and organise an art fund of sorts.

M.V.H.: Did you manage to take any of your work with you?

L.K.: No, most artists have lost their archives, I’m no exception here. I paint, and my pieces are usually quite big in size. I had to leave everything in Kyiv. But it’s very important for me to keep on going during the war, to work with cultural institutions, because a country that manages to preserve its art system is a strong country. It makes a big difference whether a country has its own working artists or not. As long as it does, it’s still alive. When I look at different societies, the first thing I am interested in are their museums, art institutions, and artists themselves. When I arrived in Ivano-Frankivsk I immediately wanted to check who else was in town. It turned out that a lot of artists from the entire country arrived there, and were quite lost and unable to work. So we started with buying lots of art supplies like canvas, paper, paint, etc. Everything brand new and very nice looking. We organised a room that we used as our collective studio. I encouraged artists to start working there with different materials, to make the most of the fact that we had a safe, comfortable, and quiet place for ourselves. I tried to rent a larger space to accommodate more people, but Ivano-Frankivsk is a small city, and there were already so many people who came from eastern Ukraine, that it was impossible, there was nothing left. Local people were approaching volunteers, giving them keys to their own apartments. To complete strangers! I was shocked to see this amazing trust and solidarity. Later the artist collective “Asortymenta room” provided us with a house outside the city, where we organised a residency for artists, many of whom are tired of listening to air raid sirens and need a peaceful and quiet space. I’m still curating this residency, it’s called “Working room”.

M.V.H.: How do you curate this project from Warsaw?

L.K.: We have many online discussions, artists in this residency managed to do a lot of work. We are preparing five exhibitions now: in Ivano-Frankivsk, Vienna, Berlin, Essen and then, hopefully, in Kyiv. It’s very important for us to be visible on the international stage. We have also created a fund to support museum workers across Ukraine who decided to stay in the shelters and basements of the museums to protect them from fire and other damage.

M.V.H.: Let’s go back to the moment when you arrived in Warsaw in the beginning of April. It must have been right after you got invited to participate in a show at the 59th Venice Biennale?

L.K.: I got a call from Venice at the end of March, when I was still in Ukraine. I was asked if I’d be able to paint seven huge paintings, because the space in Venice was very big. In Ivano-Frankivsk I made a large painting called “Max is in the army.” I was asked if I could continue the series for the Venice Biennale. I said “Sure, of course I could”. But as soon as I hung up, I thought, “Oh. My. God. How am I going to do that in three weeks?” I went to a bar with a friend, had a beer, and I remember I kept saying that there is no way I can do it in such a short time.

M.V.H.: So how did you do it?

L.K.: I called the curator from Ujazdowski Castle and told her I needed a big studio. When I arrived in Warsaw I spent a few days looking for stores with art supplies. I also realised that for the first time I will have to work on the floor, because the size of these paintings is 4 meters by 2 meters. I eventually painted four of them, and it was really important for me that they will be shown on as an installation.

M.V.H.: You often exhibit your paintings in this way, using them as objects in the space, as opposed to the traditional way of hanging them on the walls.

L.K.: Yes, I was very glad that we could use my approach in Venice. Before I received the invitation, I was really worried whether I’d still be able to look at art at all. Every day we are exposed to some very graphic content on the internet. What you see in Western media is nowhere close as hardcore as what we see in some channels on Telegram [a messaging app popular in Eastern Europe]. I follow some channels run by ex-soldiers or army consultants. It’s really brutal, they post a lot of images of dead bodies. Sometimes they’re civilians, but other times they’re Russian soldiers. I know it’s abnormal, but as any Ukrainian will tell you now, I feel a sense of satisfaction when I see a dead Russian soldier. It’s because war dehumanises. It all becomes a new normal.

M.V.H.: You work with the theme of dehumanisation of war quite a lot.

L.K.: That’s how I see the role of an artist. To rethink what is happening, why is it happening in the 21st century, how this became the new normal. Suddenly it’s acceptable to show and to see dead corpses everyday. Because of the daily exposure to this content, I was really worried that I won’t be able to look at art.

M.V.H.: But it turned out to be possible?

L.K.: Yes, however, I can see how my perception of art has changed. I look at some works of art I’ve seen before, and I see them differently now. It is quite clear for me that my sensibilities have been affected a lot since the war broke out.

M.V.H.: Painting has always seemed to me as a great therapeutic activity, but for a person who does it for a living, does it still have this quality? Do you paint more during the war than before?

L.K.: I never used painting as therapy. I always make sketches and write a bit before producing the piece, which itself is a statement. But now I think it does have a therapeutic effect on me, it helps me to create a certain distance from the world outside. After looking at images of corpses of soldiers on a daily basis, I started to work with these images. I started looking at them from an artist’s point of view – I look at the colours, at the shape of a dead body. I graduated from the National Art Academy in Kyiv, where I studied anatomy for two years. I look at those corpses now as a study in radical anatomy.

M.V.H.: I have realised that although I still follow the news from war as much as I did at the beginning, I tend to skip photos and videos now, I just cannot take those images anymore. And you decide to work with them. Don’t you feel emotionally exhausted?

L.K.: For me text is much worse than images. I can’t read about violence, rapes and killings anymore. I find text much more dangerous, because it makes your imagination work, it trains your brain in imagining horrible things, and that is poisonous for your emotions. Dead bodies are peaceful, they’re already done with this. Even when they bear signs of torture, it’s over when you see them, they are not suffering anymore. When you’re reading , you are right there in the process of the events. When I was reading about the Bucha massacre, I couldn’t stop crying and had to say “Stop!” out loud to myself to distract my mind with my voice.

M.V.H.: Can you tell us about your painting process? How does it start?

L.K.: I very often start with a photograph. The source of a photograph is particularly important for me, whether it was taken with a mobile phone, whether it is some footage found on the internet, or whether I took it myself. I have used some photographs of soldiers in my work before, but now during the war it is forbidden to take photos of soldiers or any military objects in Ukraine. Suddenly photography became a very dangerous medium, which can be used as a weapon. This brings up the question of what we depict and what we hide from the public eye. My husband Max is not allowed to make any video calls or take any pictures that reveal their surroundings. I asked him to take a photo of himself, so that I could see what he looked like. And so he did. He was wearing his civilian clothes, which he did all the time during the first months of the war, but he had a gun in his hand and was saluting with the other hand.

M.V.H.: Was he allowed to send this picture to you?

L.K.: Yes, because it was taken with a plain background, not revealing their military position. I was pretty shocked when I saw it. His body language has changed drastically.

M.V.H.: That was the origin of “Max is in the army” series.

L.K.: Yes. One of my goals as an artist now is to link military life with civilian life, so that everyone in the world can relate to it. It’s just a normal guy wearing his everyday clothes – jeans, trainers and a hoodie. Everyone can relate to that, he could be any guy anywhere. We get to see a transformation of this person that comes with the military gesture. I used this image to contrast a peaceful life with the changes brought on by war. I also used the image of a mobile phone, which has became a very important tool during the invasion. We get siren alerts on our phones. We have all this data on our phones. The pictures we take with our phones can be very dangerous, but they can also be used as proof of the truth about the war. When he calls me, he can’t say where he is and what they are doing. So I had to use my imagination. I asked him to take a photo of another lieutenant, and he looked just the same – jeans, trainers, a hoodie and a gun. For a moment I even thought it was funny. And surreal. Phones have become such powerful tools. We write history with our phones.

M.V.H.: You made a painting of a mobile phone with a siren alert on.

L.K.: I made it in March, while still in Ukraine. The idea was to leave it unfinished, because I imagined that I might have to stop painting at any moment. And just a couple of minutes after I started painting, the sirens took off and I had to run to the shelter. There is a video recorded by my colleague of me painting super fast with the sirens blaring in the background.

M.V.H.: Did you manage to bring it to Warsaw?

L.K.: Yes! Actually there is a pretty amazing follow-up to that story, because a Polish friend of mine, artist Mikołaj Chylak, finished this painting for me, as a symbolic gesture of care. A helping hand from the West to Ukraine.

M.V.H.: That’s a beautiful metaphor. It must be a very difficult task though, to finish another artist’s painting.

L.K.: Absolutely. But it’s an important political gesture. I’d like to thank all the Polish people who are amazing and make us feel at home in their country. When I crossed the Ukrainian – Polish border I felt like a baby – everyone I met here wanted to take care of me.

M.V.H.: I’m glad to hear that. You have been working with the theme of war for many years, since the annexation of Crimea in 2014.

L.K.: I was preparing a big show in the National Museum in Kyiv of all my war-related works. It was meant to open in June 2022, but of course now it’s cancelled. One part of the show was going to be my personal experience of war, which I compared to the one of my grandparents during World War Two. My grandfather was also a painter, so I compared his depiction of war with my own. I also compared the point of view of an artist with the one of the shooter. I have a studio in Kyiv, which used to belong to my grandfather, and just opposite of it there is a military base. The studio is on the 6th floor, so I really had the perspective of a shooter, looking down at soldiers, zooming in on them with my phone. I could actually spy on them. I thought that the difference between mine and a shooter’s point of view is that I, as an artist, focus on the surface of the body – the colours, the shape, etc, whereas a shooter focuses on internal organs, on penetrating the body. There is something erotic to it, that’s the nature of war – to penetrate enemy’s body with a bullet, to transgress the surface of a body. But when the war started I understood that it’s not erotic, it’s pornographic instead. Images of dead, mutilated bodies cross our personal boundaries. When you look at them, sometimes with their internal organs visible, you understand that you look at something very intimate, you can see everything, it is like watching war pornography. I keep thinking about all the children who have seen dead bodies lying around on the streets of Bucha and Mariupol and I just cannot imagine what impact that will have on their lives. When my grandfather was 90 years old, he told me that he still remembered dead bodies lying on the streets during the Great Famine 1933, when he was just 11 years old. He said it was the most powerful experience of his life. Those images stay with you forever.

M.V.H.: Will you continue the “Max is in the army” series?

L.K.: I can’t, because Max doesn’t look like this anymore. He wears a uniform and a bullet-proof vest now, sometimes he even sleeps in it. I don’t recognise him in this outfit, it looks as if his face and his body belong to two different people. I think a lot about the contrast between physical contact with war versus digital imagery. In Warsaw I often go to a military store to buy some equipment for my husband and his colleagues, which I send to Ukraine. Every time, the physical contact with war equipment is a shock for me. I will try to work with this theme, the material aspect of war.

M.V.H.: Don’t you ever want to work with any other theme?

L.K.: I don’t think I could. It’s about the perspective you have, how you see the world. Renaissance artists used a window view in their work, painting what they saw through their windows – trees, sky, city landscape. And from the windows of my studio in Kyiv I’ve always seen a military base. So I like to think that I use this very traditional perspective, like a window view, but the view happens to be on war.

M.V.H.: You teach in Kyiv Academy of Media Arts. What is happening with the school now? Is it closed?

L.K.: Yes, we have put it on hold. There was shelling about 200 meters away from it recently, so it’s definitely too early to reopen. Anyhow, I can’t imagine discussing art history with students now, it’s not a good time for such things. In my opinion, only children should continue with online school, and all adults should do volunteer work to help us survive as a society and to win this war.

Support Ukrainian Artists

Asortymentna Kimnata is an art institution from Ivano-Frankivsk that has organised a lot of impactful initiatives since the beginning of the Russian invasion. These included evacuating artworks from eastern Ukraine, organising art residencies for displaced artists, workshops for displaced kids, and fundrising to support the Ukrainian army.