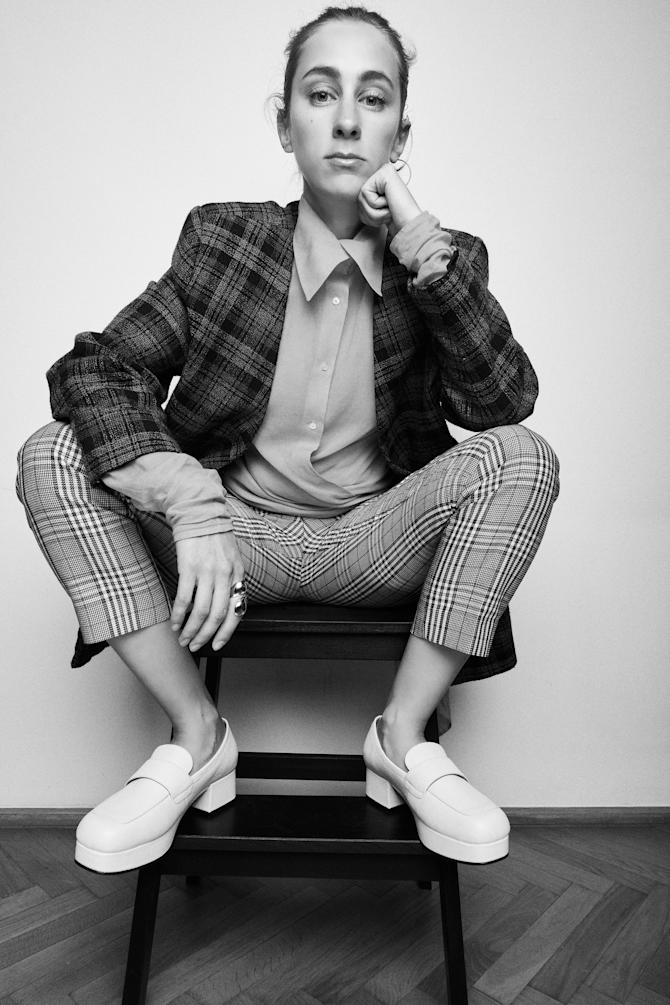

Maria Jeglińska-Adamczewska

by: Maja von Horn

Photography: Piotr Maciaszek

When in 2008 Wallpaper magazine put her on a list of most promising young talents in design, a career abroad was within reach for Maria Jeglińska-Adamczewska.

She had just graduated from the prestigious ECAL in Lausanne and worked under the eye of several stars of global design: Galerie Kreo in Paris, Konstantin Grcic in Munich, and Alexander Taylor in London. But then she unexpectedly returned to Poland.

Now she designs furniture, lighting, and consumer products, and has curated multiple exhibitions showcasing Polish and global design. She is also the art director of the Arena Design fairs in Poznań, where she promotes Polish designers and furniture manufacturers. Her work has been shown at the most important international design exhibitions and fairs, including Salone del Mobile in Milan, the London Design Festival, Centre Pompidou in Paris, and London’s Barbican Art Gallery. Maria works with many international brands such as Ligne Roset, Vitra, 1882 Ltd., Kvadrat, Trame Paris. In Poland, her collaborators include the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, the Autor Rooms hotel, and the furniture maker Plato.

Vase Man, Autor Rooms, 2018

Photo: Pion Fotografia

Maja von Horn: What are you working on right now?

Maria Jeglińska-Adamczewska: I recently took part in “Connected,” a project run by the American Hardwood Export Council, an organization that promotes wood that comes from trees that grow in the US, like red oak, maple, and American cherry. AHEC works with European designers through various projects during the London Design Festival. This year they invited nine of us, each designer from a different country. Our designs will be manufactured by the brand Benchmark and exhibited in the Museum of Design in London.

M.v.H.: What does your work look like during the pandemic?

M.J.A.: I can’t go to Benchmark in the UK, so we do all of our meetings online. Other than that, it’s not all that different, because I usually do all my designing far from where the products are manufactured. For this project, I designed a very simple table and chair from cherry wood. This was in the early days of the pandemic, today I'd do it very differently. But I’m glad I got to capture the fleeting mood of the time. During lockdown, many people yearned to go back to the simplest physical activities: baking bread, gardening, cooking. I also craved simplicity. I stripped the design of all the unnecessary layers and left only what was essential, so that the chair be a chair, and the table be a table -- nothing more. I picked cherry, because it has a nice grain and a beautiful warm color. Not many designers opt for it these days -- not because there’s a shortage or that it’s expensive, but because oak and ash are in style. Cherry, along with maple, was much more popular twenty years ago.

M.v.H.: What do your versions of a simple chair and table look like?

M.J.A.: They are based on an arch. I didn’t want them to dominate the space around them, but rather form a background for everyday life. I’m interested in making objects that occupy a space between architecture and furniture design. I wanted for the chair to give the user a sense of safety, to hug you when you sit down. I think we’re all looking for a sense of safety during the pandemic.

M.v.H.: You launched your studio, Office for Design and Research, eight years ago in London. Today you live and work in Warsaw. What does the conceptual and research side of your work look like?

M.J.A.: In addition to design, I do research, which I define broadly -- it can be simply drawing, which for me is a form of artistic exploration, or a curating opportunity. My first such project was an exhibition called “Ways of Seeing/Sitting” which I curated and designed at the Design Festival in Lodz in 2012. The intellectual work I do to prepare a show later translates to the objects I design. In 2016, I was the co-curator of the Polish pavilion at the first London Design Biennale.

M.v.H.: Aside from commissioned work, you have projects in your portfolio that were your own initiative. The newest one is “Avant-Garde: Patterns 1920-2020,” which you created this summer.

M.J.A.: I was able to do this project thanks to a three-month grant from the Polish Ministry of Culture to help artists and designers in different mediums. There was no assigned topic -- you just had to be able to view the work online.

M.v.H.: Where did you get the idea to create patterns inspired by the Polish avant-garde movement?

M.J.A.: One inspiration was the Polish pavilion at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris in 1925. Another was Praesens, a group of architects and artists who were active at exactly the same time, but had completely opposite ideas and themes. The Polish pavilion was created in opposition to the Polish revival movement, new technologies, and modernism. Its creators promoted Polishness, used folk motifs. The Praesens ideas were much closer to the Bauhaus school. I thought comparing these two groups would be very interesting, although they’d both probably be outraged.

M.v.H.: You created your own patterns inspired by these movements.

M.J.A.: The triangle was a recurring motif at the 1925 Polish pavilion. The painter Zofia Stryjenska decorated the main room, and I found the way she stripped down various forms to geometric shapes fascinating. I bounce off these motifs and colors, and create my own patterns.

M.v.H.: What does your design process look like?

M.J.A.: It usually depends on the client and on the assignment. I recently worked for the Polish brand Plato. I started from designing wardrobe systems and accessories, but the project later evolved, and we added storage furniture. The world of closets is very conservative -- I wanted to go beyond the clichés and freshen it up a bit. The leading theme was textured glass -- its structure, dimensionality, feel.

M.v.H.: You recently also designed rugs for the French brand Trame Paris.

M.J.A.: This was a very interesting project. The brand was founded by French Moroccans, and its designs explore the craft of the Mediterranean region. The first collection is dedicated to Morocco. I designed pottery, rugs, and blankets woven using a traditional Berber technique. New color versions of the rugs will be available in the fall at the Paris department store Le Bon Marché and online.

M.v.H.: How did they find you?

M.J.A.: Through Valentina Ciuffi, the founder of the Milan agency Studio Vedet, the art director for this project. They chose an Italian designer, a Swiss-French one, and me. We’ve been working only on the color scheme for the last year, and that process isn’t even done yet. They took us to a Moroccan town in the Atlas mountains to see how Berber women weave the rugs. They do it at home, thanks to which they can take care of their family. The size of the carpet often depends on the size of their room.

“A good designer can design anything, it’s in the profession’s DNA.”

M.v.H.: You design furniture, lighting, consumer products, rugs, as well as interiors. Is there something you wouldn’t take up?

M.J.A.: I don’t think so. A good designer can design anything, it’s in the profession’s DNA. I learned this in the Paris, Munich, and London studios where I worked before I started my own. I approach commissions differently than a person who specializes in one kind of work. I try to question the status quo of a given category or the material, to freshen how we think of it. This is what differentiates a designer from a craftsperson. And thanks to this I keep learning about new materials, techniques, ways to collaborate with different brands. Sometimes I get a brief with specific requirements, at other times the collaboration is based on a back-and-forth conversation, and I work on the brief along with the client.

M.v.H.: Do you get this versatility also from the schools you graduated from?

M.J.A.: For sure. First I went to school in France. It’s where I was born [in Fontainebleau near Paris -- ed.], where I spent my entire childhood in Paris. Later, in the early nineties, my parents decided to move back to Poland, where I went to the local French school. But as a teenager I felt lost in Poland. Moving from Paris to Warsaw in 1991, when I was eight, was a big culture shock -- like going from a color movie to a black-and-white one.

M.v.H.: What do your parents do?

M.J.A.: They met in Paris. My mother studied sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts there. My father is a publisher, he ran a Polish bookstore by the Seine.

M.v.H.: Is your mom still a sculptor?

M.J.A.: No, I have four younger siblings, so she took care of the house and helped dad at the publishing house. Because her family is sprinkled around the world, I was able to travel a lot, which was a big privilege.

M.v.H.: You went back to France after high school.

M.J.A.: Yes. I did a year-long course that prepares you for university, helps you build the required dossier. I didn’t get into ENSCI, the school of my dreams in Paris. Instead, I landed in the Academy of Fine Art and Industrial Design in Reims, where I went for three years. Many of the professors there worked for the Memphis group. They emphasized drawing, exploring your topics by drawing.

While it’s hard to recognize where a designer is from just by their work these days, it’s quite easy to pinpoint the French design methodology -- thinking by drawing.

M.v.H.: You have a degree in industrial design from the prestigious ECAL in Lausanne.

M.J.A.: It was a two-year MA program. I learned how to work by myself and on my own account. They didn’t have traditional classes, we had one common room to work in, and we had to come up with our own workload and its organization. At first it was difficult, but later, after I graduated, it turned out to be very useful. We could participate in workshops, work with different brands and designers. After my first year I went to do a year-long internship in New York.

M.v.H.: What studio was this?

M.J.A.: These two crazy New Yorkers. He was Russian, she American -- they made up Boym Partners Studio. I later went back to Switzerland, and after graduating I did another internship at Galerie Kreo in Paris, which makes limited edition furniture, and focuses on conceptual and research work.

M.v.H.: You also did an internship at Konstantin Grcic in Munich and Alexander Taylor’s in London. What was the most important lesson for you?

M.J.A.: At Konstantin’s I learned how to ask the right questions at the outset of every project and how to choose specific tools. I understood that as a designer I don’t define myself through the medium I work in, but a methodology that lets me work with any object.

M.v.H.: What, for you, is a well-designed object?

M.J.A.: I don’t like it when objects force me to behave a certain way. What you have in your home should be an extension of your body, like a prosthetic limb.

M.v.H.: You’ve designed for many well-known brands. Which of your projects has been the most commercially successful?

M.J.A.: I’m only starting out, I have a long way to go. The tables that I designed for Ligne Roset have been in production the longest out of my designs. But as for commercial success, I think it’s too early to say.

M.v.H.: What about your work for Vitra?

M.J.A.: I designed for them a line of home accessories inspired by the four elements — water, fire, earth, air — called “Portable Landscape:” end tables, stools, flower pots. I did the research for this project before the pandemic, so it might be somewhat outdated. Its conclusion was that by 2050, two-thirds of all humans will live in cities, and our contact with nature will be very limited. So I wanted to bring people closer to nature and its elements, hence the “portable landscape.” So far we only have the prototypes, they are not in production yet.

M.v.H.: What’s the hardest thing about this job?

M.J.A.: It’s a very difficult market, much more difficult than in the past. That’s why so many designers decide to launch their own brands, manufacture their designs on their own. It’s also harder to collaborate with well-known manufacturers, and even when that happens, it’s difficult to make a living, since your income depends on royalties. This system of collaboration was created in Italy after World War Two, when you had to start all over again, and there were very few designers. Today design is a popular job. It’s easy to showcase your work in the media, but that often doesn’t translate to money or to assignments. They warned us in school that it would be a difficult job.

M.v.H.: So are you thinking about doing your own manufacturing?

M.J.A.: Five years ago I would have said that absolutely not. But I think about it more and more often. I definitely would not want to stop working with brands — I like it a lot, I learn a great deal while I’m doing it, because I come into contact with assignments that I never would have given myself, I meet a lot of interesting people.

M.v.H.: Why did you decide to come back to Poland after such a promising start to an international career?

M.J.A.: I came back at the end of 2011, because in London, where I lived at the time, the effects of the 2008 financial crisis were still very noticeable. I didn’t want to return to Poland, but it turned out to be a very good decision. Our country is not at the same level of development as the West — the market is still evolving, there is still a lot to do. Poland is one of the largest producers of furniture in the world, many Western brands manufacture their products here. I hope that more and more Polish manufacturers will start launching their own brands.

I’m the art director of the Arena Design fair in Poznań, whose goal is to support the Polish market. The hope is that our country stops only being associated with the “Made in Poland” label. We want to promote Polish design in the way that Scandinavian countries promote theirs — through furniture. I believe that we can build a strong Polish brand if our furniture manufacturers change their approach to be more original. I know that I have a bigger role to play in Poland than abroad. There are many more people like me there, and here I feel like I can really affect change. I dream that one day we’ll be able to outfit a house solely with Polish brands.