Text: Maja von Horn

Photography: Joseph Seresin

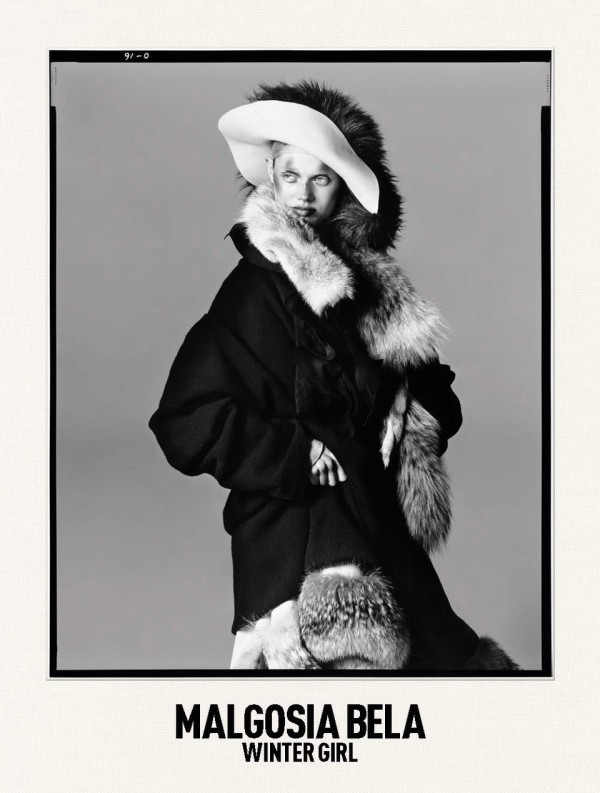

When I arrange to speak to Małgosia Bela on Zoom about “Winter Girl”, a book about her 25-year career, published by 77 Press, we have to schedule two calls. It’s fashion week season and Małgosia has to travel from Milan to Paris. She says she’ll be back in her Warsaw apartment in a month, her calendar is as full as it was at the peak of her career. But the idea to compile a book came out of a slower period. It was summer, and she was getting fewer assignments, which her agent aptly explained: she is a “winter girl”. “My look is much better suited to turtlenecks than bikinis”, she says. When I show her the 2009 Pirelli calendar I recently found in my basement, in which she is pictured hanging from an elephant’s tusk, Małgosia recalls that the story of that trip to Botswana was the first one she’d ever written down. She writes, in fact, very poignantly – in addition to expertly playing the piano (a moment captured in the book by Steven Meisel), acting in movies, and of course, being a supermodel – and her intimate recollections are what makes “Winter Girl” stand out from other coffee table books.

Maja von Horn: “Winter Girl” has made me realize that it’s been 24 years since I admired you in the March edition of the Italian edition of Vogue, the so-called “The Małgosia Issue.” A career like that is rare in fashion.

Małgosia Bela: It was a matter of several factors. First, it was luck, good timing – I was discovered at the right moment. Afterward, it was about what I put into it, and for that I can thank myself and my parents, who gave me my work ethic. The third element is good management, which is particularly important today. These days you can make a career out of nothing, some dumb PR which you then just keep hyping and hyping. But a career like mine has to be sustained in a smart way, steered in such a way so that you don’t burn out, balancing edgy editorial work with commercial jobs, so that you can make a living. I’m lucky that I have agents who understand my strengths and who ensure that I’m not required to do anything I’d feel uncomfortable with. Ten years ago there was pressure for me to open an Instagram account. I still haven’t done it.

M.v.H.: Are you talking about your agent in Poland?

M.B.: No, but Darek [Kumosa, the founder of the modeling agency Model Plus – ed.] has had his hand in this, because he directed me to good agents abroad. My career in Poland is non-existent, I never accomplished anything here and Darek quickly realized I have nothing to look for in the country. When he sent me for a shoot for one of the Polish magazines, people thought I was a cleaner who came to tidy up the studio. My current agent, who is younger than me, and without whom this book would not exist, understands me so well, we’re on the same wavelength. No algorithm would be able to replicate that understanding, the human element is indispensable. AI won’t get my sense of humor or my cynical approach to certain things. This book is a celebration of human creativity and collaboration with wonderful people.

M.v.H.: What separates this book from other fashion coffee table books are your words. Ten essays, filled with surprising details and anecdotes about your early days as a model and your work with the biggest names in the industry. Did you take notes or keep a journal over these 25 years?

M.B.: No, I never took notes. The ten essays in the book are short, all of them under 1,500 words. Just like my husband [director Paweł Pawlikowski] makes movies that cannot be longer than 83 minutes, I have this magical limit of 1,500 words – I can’t do more than that, I start rambling and it has to be edited down. I’d recount these stories to my friend Filip [Niedenthal, founder of 77 Press, the publisher of “Winter Girl.” – ed.] because he was always interested in my career. I call him “Filip Full of Trivia,” because he remembers all the names and details. He was a very good listener, he laughed politely at my stories, and acted as a therapist who sits and listens. Meanwhile, I was arranging these stories in my head. When you had to sit down and write them up, that was a horrible moment. I’ll do anything – clean out the closet, vacuum, take the dog for a walk, go shopping, make dinner – to avoid sitting down and writing.

M.v.H.: That’s like most people who write.

M.B.: I had to put some effort into it, otherwise it would’ve been just a vanity project that Filip could’ve put together on his own.

“When [my agent] sent me for a shoot for one of the Polish magazines, people thought I was a cleaner who came to tidy up the studio.”

M.v.H.: Nearly the entire generation of great photographers you’ve worked with over these last 25 years is no longer with us – Richard Avedon, Peter Lindbergh, Irving Penn (who never took your photo, but who gave you an important life lesson, which you write about in the book). How do you compare working with them and the new generation of photographers?

M.B.: This book is a summary of a certain era. What today is a luxury, used to be the norm. In the past, we had two days to take five photos. During Avedon’s photo shoots, the first day was for searching, trying things, looking for ideas. There was no moodboard, maybe there were some inspiration materials, but not specific pictures. Now, when I come to the studio there’s a moodboard with my photos from more than a decade ago. And a request from the client: “Let’s do that.” Copy-paste. I miss the creative exchange for which we used to have time at work. It didn’t mean that we took vacations together afterward or even went out to dinner – I don’t have these relationships in the industry at all. But I also don’t want to only complain that it used to be so great in the past and now it’s horrible. There’s nothing we can do about it, it’s a matter of technology and the direction the world is heading. I still have encounters that knock me off my feet, like a recent – not yet published – shoot for W magazine with the stylist Joe McKenna and the photographer Jamie Hawkesworth. It’s as if we went back in time 25 years. No moodboards, just the clothes and the space. No pressure to take dozens and dozens of photos – we could take five or six, as long as they were good. Everyone was focused, no one on their phone. Jamie wasn’t even taking Polaroids, only calling over Joe, the stylist, from time to time to look through the lens and see the frame. No one knew what the images looked like. The photographer had enormous respect for the stylist, and the stylist for the photographer. I hadn’t experienced anything like that in a long time, and I was very touched that this is all still possible. Because it’s so rare these days, I value it all the more.

M.v.H.: Speaking of Avedon, about 20 years ago you said in an interview that he recommended you watch the movie “Come and See”, which ended up having a powerful effect on you.

M.B.: Yes, he literally gave me the movie. He said “You’re from those Eastern regions. I wonder how it’ll affect you”. He also gave me books to read, we had a pretty special relationship. I wouldn’t call it friendship because he wouldn’t confide in me, and we didn’t go into intimate details. But he was my mentor. If we were to speak Polish, I’d call him “Sir” [a standard way of referring to someone we’re not intimately familiar with – ed.] I had enormous respect for him, and I was fascinated by the fact that at 80, he would get excited like a little kid, literally give a little jump with every photo. I feel embarrassed by that kind of thing, especially when I feel jaded or tired. He had incredible energy and passion.

M.v.H.: I was in London at the time and I bought the film on DVD on your recommendation, and shortly thereafter I met my now-husband. On our first date at home I showed him “Come and See”.

M.B.: And that’s how you made him fall in love with you!

M.v.H.: We were both shaken up by the movie, but yes, I think he was impressed, and you’ve had your role in that.

M.B.: I get goosebumps thinking about that. I actually met Małgośka Szumowska [Małgorzata Szumowska, Polish film director – ed.] some time later. When she asked me what movies I watched, because she was looking for a girl for her feature “Ono”, I said that I’d recently seen “Come and See”, and she was like “No way! That’s my favorite movie”. I got a part in her movie, and later she introduced me to my now-husband Paweł. Avedon is behind all of that.

M.v.H.: But you do like to work with young photographers as well.

M.B.: I prefer those who know what they are doing. From time to time, someone from the younger generation has a specific vision, and they push for it. That’s a good thing. But it’s harder for me to get along with them, this younger generation is brought up in such an image-heavy culture, which is very different from my experience.

M.v.H.: But isn’t it that when a photographer is less experienced, you have more of an opportunity to be creative?

M.B.: The thing I dislike the most is working with someone who is starstruck. No matter what I do, it’s “amazing,” and I find that really annoying. That’s when I do have to take control of the entire thing. That’s the downside of working with people who could be my children – they are shy and overwhelmed by my resume. But if there’s a young person who has a vision pertaining to me, and doesn’t care at all about my past work, but instead is focused on what we have together right now, that can be very fresh, fun, and creative. And that’s important, because at my age, it’s not like whatever I do is going to look good. I was never completely photogenic, like Kate Moss for instance, whom you could put somewhere in the corner and she’d look amazing in a 2D picture. I’m not like that.

M.v.H.: Aren’t you being a little coy?

M.B.: No, I’m serious. That’s why I think I’m a very good model. I know what to do to make things look good, I know how to get in sync with what is ineffable in the set design, in someone’s idea, or even just the garment in a plain, white studio. It sounds trite, but I can see how rare it is in photos. My idol has always been David Bowie, I’ve always wanted to be like him. What he does in photos, what he wears, he simply becomes it. He’ll come out on stage with something enormous on his forehead and that’s authentic. When I was young I dreamt of being an actress, and instead I’m like an actress in a silent movie.

M.v.H.: But you have starred in several movies. Were any of your roles particularly important for you?

M.B.: I don’t think I attach a lot of importance to any of them. I’m usually cast like I was in the film “Suspiria” [dir. Luca Guadagnino] – as some sort of monster or castrating mother… “Suspiria” was actually a great experience because I could use my modeling skills like sitting completely still for five hours as they apply makeup or stick stuff all over me, or not eating or drinking for 12 or 18 hours. I don’t really have acting abilities, but I know how to embody. I may not have the craft, but I have some emotional resources and I’m randomly able to use them. But I always think of myself as an amateur. My parents talked me out of acting when I was 13. They said I was too tall and had a speech impediment, so that I better focus on playing the piano. And that’s what I did, but I had such bad stage fright during performances that my career as a pianist was doomed. It wasn’t until I became a model and stood in front of a camera that I got rid of the stage fright.

M.v.H.: You started out in the era of supermodels, when your type of beauty wasn’t seen as “commercial”. Now, you seem to be more versatile than ever.

M.B.: Have you seen Ruben Östlund’s last movie?

M.v.H.: Yes, “Triangle of Sadness”.

M.B.: There’s a scene early on in the film, where during a casting male models are instructed to do “H&M”, so to make a “commercial” face, and “Balenciaga,” which means a more edgy one. I’ve actually booked numerous jobs for both of these brands in the last two decades

“My idol has always been David Bowie, I’ve always wanted to be like him. What he does in photos, what he wears, he simply becomes it.”

M.v.H.: Filip Niedenthal says that you push yourself to the limits.

M.B.: He knows best.

M.v.H.: Are you a workaholic?

M.B.: No, I’m just a professional – and a perfectionist. It’s not obsessive, but if I know that something can be done better, then let’s just do it better. That’s standard for me, it always has been. My son doesn’t take well to that, he sees it as pressure, as pushing, but I don’t perceive it that way at all. According to the younger generation’s benchmarks I’m intense and demanding, but for me it’s normal. I guess I was pressured in the same way.

M.v.H.: But it’s also self-discipline. Have you been able to impart some of that onto your son?

M.B.: Yes, now that he’s moved to Berlin for school, he does the same thing. And that’s good, because I remember that when I found myself alone in New York without any money, in a world that I didn’t know at all, my saving grace were those lessons from my parents, those tedious, horrible lectures that were meant to inculcate values.

M.v.H.: “Whatever you do, do it well.”

M.B.: My son made me realize that not everyone works well under pressure, but for me it’s vital. My husband says that modeling will save my life. I know I can’t drink wine with dinner – as I am prone to do – if I have work the next day. I don’t see it as this huge sacrifice, it’s how I function in this world where there’s constant pressure to be in shape, look a certain way, manage lack of sleep, jet lag etc.

M.v.H.: In the book you write that you felt guilty that you were making more money lying around on the beach in the Bahamas than your parents could make in their entire careers.

M.B.: I recently saw this new documentary about supermodels in the 1990s, and a lot of it is about money. I had no concept of how much money there was in this business. My mom borrowed some dollars from a priest she knew so that I could have at least something when I first arrived in New York. I spent a fifth of that just for the cab from the airport to Manhattan. It wasn’t about the money for me, and I think this was less due to how my parents raised me, but more due to growing up in a communist country. When I was 21, I was still in college, which was free in Poland. I had a scholarship. My parents had this approach that as long as you’re in school, you don’t have to worry about rent. I have the same attitude with my son. I came to New York for the adventure, not for the financial boon. I didn’t even have a bank account. I didn’t realize that I wasn’t getting money for lying around in the Bahamas, but for the right to use my face. Several years passed before I understood this. I thought it was all like a free vacation. So when I got a makeup contract with Shiseido – which actually happened quite early on – and suddenly $150 became $150 plus some zeros, that was shocking. It didn’t sit well with me, I had some sort of Catholic guilt. I remember that my parents were making something like $300 a month at the time.

M.v.H.: In the Peter Lindbergh story, you recall how for your first Christmas back in Poland you brought your parents an issue of Vogue with your picture on the cover and $10,000 in an envelope.

M.B.: I brought that much because that’s all you could bring over in cash. Maybe I was already too old to be awed by the money, or it was my upbringing. I never spent money on clothing, the itch to get dressed up was fully or even doubly satisfied at work.

M.v.H.: Soon after, you were looking at the falling towers of the World Trade Center from a Manhattan studio.

M.B.: Filip was staying with me in New York, and I remember that we felt like the world was ending, that fashion was over, that the industry is a joke, that it’s total excess. It happened during New York’s fashion week, and at first all the shows were supposed to be canceled, then rescheduled, and then they settled on still having them, but without music, and calling them “presentations” instead of shows. And thus we observed, in horror, how everything went back to normal within a week.

M.v.H.: It was similar during the pandemic. At first there were so many conversations about not flying so much, that it’s unnecessary and harmful to the environment.

M.B.: The pandemic caused an enormous technological step forward. I was shooting a Max Mara campaign with Steven Meisel: he was in New York, and I was in Paris, along with his assistants, all on Zoom. We thought that it could stay like that, that maybe we don’t have to fly as much, that we should be limiting our carbon footprint. And then everything came back with a vengeance, there are even more shows, on all the continents. It’s terrifying.

“[My son] paid a large price for me to be in all these photos. So it’s also a tribute to him.”

M.v.H.: Alongside work from the biggest fashion photographers in the world, in the book there’s also a portrait taken by your 19-year-old son, Józio Urbański. How did that come about?

M.B.: This is another story about how to turn around what seems like a disaster into something good. When I asked the photographers to let me use their photos in my book, they all were very enthusiastic and happily gave me the images. Except for one. I wanted the book to have 100 photographs, and we were missing a single one. We could’ve just slotted in another image from Tim Walker or Steven Maisel. But we wanted to maintain the good vibes around the book – it was a friendly DIY project. And then I remembered about the photo that Józio took testing out some camera. My hair is tied back, which is my signature look, I’m not wearing makeup, the photo is a bit underexposed – but thanks to this image, the good karma of the book has been preserved. I thought it would be cool that my son would be in it too, after all he is also part of my legacy and my pride. He didn’t have an easy childhood, there was a lot of instability, uncertainty as to when I leave again and when I come back. He paid a large price for me to be in all these photos. So it’s also a tribute to him.

M.v.H.: He didn’t want to follow your footsteps and become a model?

M.B.: Absolutely not, although casting directors are constantly asking me about it. But Józio, like every self-respecting young person, is interested in philosophy and would like to live in an artistic commune. He is studying sound design in Berlin – he definitely wants to be an artist, but also to have a trade, which I am very happy about. He got this combination of pragmatism and talent from me, although he has more talent, and I have more pragmatism. But I was able to convince him – or rather bribe him – to do a large Christmas campaign with me, which will premiere this fall. He was very embarrassed, but he did it.

M.v.H.: How did you bribe him?

M.B.: You know, even if you’re anti-capitalist, you have to buy that guitar or piano with something.